Click here to download a PDF version of this spotlight.

» Tomato spotted wilt (TSW) is an economically important disease of peppers caused by the tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV).

» The tomato spotted wilt virus infects a wide range of plant hosts and is vectored by several thrips species.

» Disease resistance, cultural practices, and insect management can help lower the incidence and severity of TSW of pepper.

The disease known as tomato spotted wilt (TSW) of pepper is caused by the pathogen named the tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV). This virus infects an incredibly wide range of over 1,000 plant species belonging to 85 different plant families. Plant species in the Asteraceae (lettuce) and Solanaceae (tomato, pepper) families are some of the most common hosts of TSWV. Vegetable crops affected by TSWV include lettuce, eggplant, onion, pepper, potato, tomato, and spinach. Several important ornamental crops are hosts for TSWV, as are several common weed species.1,2 Tomato spotted wilt was first reported on tomatoes in 1915 in Australia. It has since been economically destructive on several vegetable crops.

SYMPTOMS

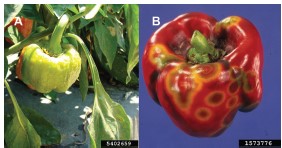

Symptoms of TSW on pepper can vary widely in severity and characteristics depending on the growth stage at the time of infection, cultivar, environmental conditions, virus isolates involved, and co-infection by other viruses.1,3 Infection at the seedling stage often results in stunting and the formation of necrotic spots or rings on leaves (Figure 1), and seedlings can die if severely infected. Leaves may develop a bronze appearance, and plants may droop or wilt. Vein necrosis may appear on stems and petioles. Severe infection may result in total loss of fruit production. Fruits that do develop may have bumpy surfaces (Figure 2A), develop necrotic spots and concentric rings (Figure 2B), and may have a distorted shape.1,3

Figure 1. The effect of pH on the plant availability of three secondary macronutrients.

Figure 1. The effect of pH on the plant availability of three secondary macronutrients.

If plants are not infected with the TSWV until they are older, symptoms may only appear on some parts of the plant, as the virus is unlikely to move into and affect mature plant tissue. Symptoms developing on older plants include leaf curling and leaves developing a pale green to yellow to purple color. Chlorotic to necrotic flecks can also develop on leaves and stems. Fruits that develop on infected portions of older plants may become bumpy, show chlorotic spots, necrotic spots, or ringspots, and may be deformed. Flower and leaf drop may occur on some pepper varieties. Irregular color patterns may develop on the fruits of infected plants.1,3

Figure 1. The effect of pH on the plant availability of three secondary macronutrients.

Figure 1. The effect of pH on the plant availability of three secondary macronutrients.

CYCLE AND CONDITIONS

TSWV is not seedborne, and plant-to-plant contact does not spread the disease. A thrips vector is needed for the dissemination of TSWV in the field. TSWV can be transmitted (vectored) by ten different thrips species, with western flower thrips and tobacco thrips being the most common vectors on vegetable crops in North America.1,2,3 The thrips vector can only acquire the virus when the larval stage feeds on infected plants. Once TSWV has been acquired by the larva, the virus persists and can replicate in the insect, and the insect can transmit the virus to susceptible host plants for the rest of its life. Both the larval and adult stages of the thrips vector can transmit the virus by feeding on susceptible host plants. The virus is not passed from infected female thrips to their eggs.1,2,3

Although TSWV has a wide host range, only the hosts on which the thrips vectors can complete their life cycles (egg, larva, adult) are significant in the disease cycle of TSW. Nearby fields of infected crops, (including lettuce, peanut, tobacco, and tomato) can serve as sources of the virus and the thrips vectors for new plantings. TSW susceptible weed species can also be important sources of the pathogen and vectors, and Bayer, the virus can overwinter on some winter annual weed species. Important weed hosts include: little mallow, sowthistle, prickly lettuce, and others.2,3,4 Summer annual and perennial weeds can serve as reservoirs of the virus and vectors when the crop is not present in the field during the spring and summer. Perennial hosts of TSWV can remain infected and serve as inoculum sources for several years.4 TSWV can be spread long distances on infected transplants and other infected ornamental, vegetable, or fruit crops.1

MANAGEMENT

Tomato spotted wilt virus can be difficult to manage because it has such a large host range and many species of thrips vectors. Attempts to manage the disease by controlling thrips are usually unsuccessful.1 Integrated management systems that focus on using disease-resistant pepper varieties, diseasefree transplants, and cultural practices that help prevent infection are usually the most effective.1,2,3

Resistance to TSWV in peppers was first identified in the 1990s, and TSWV resistant pepper varieties became commercially available in the early 2000s.2,4 Resistance to TSWV in peppers can be conferred by the Tsw resistance gene. Tsw is a single-gene form of resistance, which is only expressed in the leaves, not in the flowers or fruit. Because the thrips vectors of TSWV often prefer to feed on the flowers, it is possible to see symptoms of TSW develop on the fruit of plants containing the Tsw gene.2 There are reports of TSWV isolates that can break resistance conferred by Tsw.2,4 Pepper plants can become more resistant to TSW as they get older.

Although attempts to completely eliminate the thrips vectors are usually not practical, strategies to minimize thrips populations can help prevent the spread of TSW within the field.2 Planting virus-free transplants is important to help prevent the introduction of TSW into a pepper planting, and monitoring seedlings and thrips populations in the greenhouse during transplant production can help keep transplants virusfree. Placing thrips-proof screens on greenhouses during the transplant production period can help keep these vectors from entering the greenhouse, as can double-door entry systems with air blowers.1,2,3 Releasing predators and parasites of thrips in the Sgreenhouse can help suppress thrips populations. It may become necessary to apply insecticides if thrips populations in the greenhouse start to increase, but these applications may also eliminate any applied beneficial predators or parasites. Externally sourced transplants and all ornamentals should be kept separate (a different greenhouse if possible) from transplants being produced on-site.2

Manage weed hosts of TSWV — including dandelion, sow thistle, chickweed, buttercup and plantain — in and around the field. Start two to three weeks before transplanting for fast-acting herbicides (e.g., paraquat) and four weeks for slowacting herbicides (e.g., glyphosate) to remove reservoirs of the virus and thrips vectors.1,2,3,4 Avoid planting near older fields of tomato and pepper, especially those confirmed to have TSWVinfected plants.3 Also, avoid planting during periods of peak thrips movement, such as during the senescence of winter annuals, application of herbicide, or when weeds are being mowed.4 Continue good weed management practices during the growing season; however, excessive weed control efforts are not likely to be cost-effective.

Using reflective mulches can help repel thrips, but these types of mulches tend to be more expensive than standard black or white plastic mulches. Reflective mulches have been shown to lower incidence levels of TSW (10 to 12% mid-season) compared to levels in areas with black plastic mulches (40 to 45% mid-season). To be effective in repelling thrips, the mulch needs to have a reflectance level of at least 70%.4

Using insecticides in the field for thrips management has been shown to be only partially effective for helping to manage TSW. Insecticides are more effective for controlling thrips feeding on leaves than for thrips feeding on flowers because thrips often feed in tight, secluded spaces that are difficult to reach with insecticides.2,4 Insecticides need to be applied before symptoms of TSW develop. Contact insecticides should be applied in the first few weeks after transplanting, while systemic insecticides should be applied before or immediately after transplanting. Insecticide applications may delay infection by TSWV and somewhat reduce the incidence of TSW, but they will most likely not completely eliminate the disease.4

After harvest, promptly remove and destroy the crop debris and any volunteers. This strategy works best if practiced regionally on a coordinated schedule.3

SOURCES

1Adkins, S. 2003. Tomato spotted wilt virus. In Pernezny, K., Roberts, P., Murphy J., and Goldberg, N., Eds. Compendium of Pepper Diseases. American Phytopathological Society.

2Cooper, A. and Meadows, I. 2024. Tomato spotted wilt virus on tomato and pepper. NC State Extension Vegetable Pathology Factsheets. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/tomato-spotted-wilt-virus-on-tomato-and-pepper

3Koike, S., Davis, R. Subbarao, K., Falk B. 2009. Tomato spotted wilt. UC IPM, Peppers Management Guidelines. https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/peppers/tomato-spotted-wilt/#gsc.tab=0

4Abney, M., Scott, J., Olson, S., Riley, D., Gunter, C., Kelly W., Langston, D., Louws, F., Sparks, S., and Chappell, T. Tomato spotted wilt virus. University of Georgia, College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences. USDA RAMP Project. https://tswv.caes.uga.edu/usda-ramp-project/management.html

Websites verified 5-10-2025

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

For additional agronomic information, please contact your local seed representative. Performance may vary, from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and environmental conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on their growing environment. The recommendations in this article are based upon information obtained from the cited sources and should be used as a quick reference for information about vegetable production. The content of this article should not be substituted for the professional opinion of a producer, grower, agronomist, pathologist and similar professional dealing with vegetable crops.

BAYER GROUP DOES NOT WARRANT THE ACCURACY OF ANY INFORMATION OR TECHNICAL ADVICE PROVIDED HEREIN AND DISCLAIMS ALL LIABILITY FOR ANY CLAIM INVOLVING SUCH INFORMATION OR ADVICE.

6411_567150 Published 06/12/2025