Click here to download a PDF version of this spotlight.

» Seeds that do not germinate when conditions are favorable may be in a state of dormancy.

» Although many commercially available vegetable seeds are not subject to dormancy, dormancy issues can sometimes affect vegetable seeds.

» Seeds of some vegetable species/varieties may experience forms of secondary dormancy if exposed to stressful environmental conditions.

Successful seed germination requires a fully developed seed with a healthy embryo and a store of food reserves, proper moisture and temperature conditions, and an appropriate oxygen concentration (soil aeration). For some plant species, the presence or absence of light may be required for germination to take place.1 When a healthy seed cannot germinate in favorable environmental conditions, the seed is dormant or in a state of dormancy.2 Plants use seed dormancy to help synchronize germination with seasons and favorable environmental conditions, and some plants use seed dormancy to allow for asynchronous germination over an extended period.3

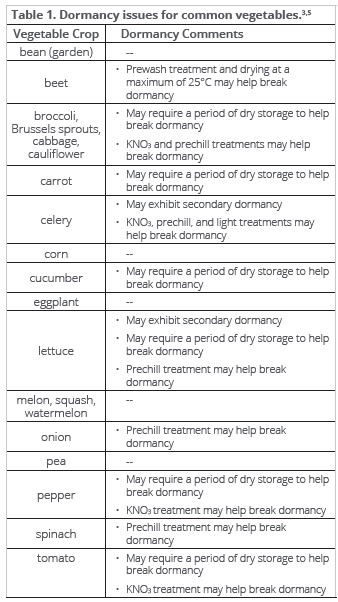

In terms of ability to germinate, seeds can be in one of three states or conditions. (1) Non-dormant seeds can germinate immediately under favorable conditions; (2) non-dormant, quiescent (inactive) seeds are inhibited from germinating by certain environmental factors; (3) dormant seeds do not germinate even when conditions are favorable. Seed dormancy can be a beneficial trait for plants in nature. For many vegetable species, seed dormancy traits have been minimized or eliminated through selection and breeding to promote rapid and uniform germination shortly after planting.3 However, some vegetable species can still express seed dormancy traits that affect stand establishment and crop production (Table 1).3,4,5

There are two basic types of seed dormancy, primary dormancy and secondary dormancy. Primary dormancy is an inherent state of a seed at the time that it is released/dispersed from the mother plant. Primary dormancy can result from exogenous factors (factors external to the embryo) such as a seed coat physically preventing a seed from absorbing water, inhibiting gas exchange, or preventing an embryo from expanding. Endogenous (within the embryo) factors, such as the presence of chemicals like abscisic acid, can prevent a seed from germinating, or the embryos can be immature at the time of release and require more time to fully develop.2,3,6

Secondary dormancy is induced in non-dormant seeds by environmental factors that are not favorable for germination after the seed has been released from the mother plant. Factors such as lack of oxygen, unfavorable temperatures, or the presence or absence of light (depending on the plant species), can induce secondary dormancy. Thermodormancy is a type of secondary dormancy induced by exposing the seed to high temperatures.2,3

EFFECTS OF TEMPERATURE

Temperature can affect the germination of many plant species. Warm-season annuals (beans, cucumbers, tomatoes) may not germinate when temperatures are too low, while cool-season crops germinate best when temperatures are lower. This is not usually a result of seed dormancy but is related to the conditions favorable for germination. However, sometimes an aspect of dormancy may be involved. Some Brassica species have a cold temperature requirement that must be met before they will germinate.1,6 The seeds of some varieties of lettuce and onions are also susceptible to thermodormancy, and they will become dormant if exposed to high temperatures, even after temperatures return to a favorable range.3

EFFECTS OF LIGHT

The seeds of some plants require a certain amount of light before they can germinate, while other plants seeds only germinate in the dark because their germination is inbibited by light.5 As a result, planting depth can affect the germination of some crops because it affects the amount of light reaching the seed. For example, some varieties of lettuce require light to germinate, and planting these seeds too deeply may result in reduced germination.6 In one study, freshly harvested lettuce seed required light to germinate, but germinated immediately after two days of imbibing water in the dark. After eight days of imbibition, the embryos did not germinate because of secondary dormancy, but secondary dormancy could be released by exposure to chilling and light.3

EFFECTS OF MOISTURE

Some vegetable crops have an endogenous type of dormancy related to seed moisture levels. These crops, including some varieties of Brassica (cole crops), Capsicum (pepper), Cucumis (cucurbits), Daucus (carrot), Lactuca (lettuce), and Solanum (tomato) require a period of dry storage after harvesting the seed before they will germinate uniformly.3

OTHER STRESSES

Some species/varieties of Brassicas are susceptible to secondary dormancy following stressful conditions, including osmotic stress and low oxygen levels. The effects of these stress factors can also be influenced by temperature. In one study, higher rates of dormancy resulting from water stress were seen at 68°F (20°C) than at 54°F (12°C).7

METHODS FOR BREAKING DORMANCY

Some seeds, such as those of some ornamental species, require procedures such as scarification (breaking or weakening the seed coat), removal of seed coats, and stratification (holding the seed at certain warm or cold temperatures to mimic overwintering or over-summering conditions) to break dormancy and allow germination. However, this is generally not needed for many commercial vegetable seeds. Some vegetable seeds may benefit from a short period of dry storage (by the seed company) to overcome some secondary forms of dormancy.3,6 Vegetable seeds sold by seed companies are usually tested for germination rates under both optimal and stressful growing conditions to determine an expected germination rate for each lot of seeds. Short-term, on-farm seed storage conditions before seasonal planting, such as storage at high temperatures, may induce secondary dormancy in some varieties and result in lower-than-expected germination rates and stand establishment levels.

SOURCES

1DuPont, T. 2025. Seed and seedling biology. PennState Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/seed-and-seedling-biology.

2Sami, A., Riaz, M., Zhou, X., Zhu, Z., and Zhou, K. 2019. Alleviating dormancy in Brassica oleracea seeds using NO and KAR1 with ethylene, biosynthetic pathway, ROS and antioxidant enzymes modifications. BMC Plant Biology 19:577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2118-y.

3Geneve, R. 1998. Seed dormancy in commercial vegetable and flower species. Seed <Technology 20 (2): 236-250. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23433025.

4Awan, S., Footitt, S., and Finch-Savage, W. 2018. Interaction of maternal environment and allelic differences in seed vigor genes determines seed performance in Brassica oleracea. Plant J. 94(6):1098–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13922.

52024. International rules for seed testing, Chapter 5: The germination test. https://www.seedtest.org/en/publications/international-rules-seed-testing.html.

6Schalau, J. 2005. Seed dormancy. Backyard Gardener. Arizona Cooperative Extension. https://cales.arizona.edu/yavapai/anr/hort/byg/archive/seeddormancy.html.

7Momoh, E., Zhou, W., and Kristiansson, B. 2002. Variation in the development of secondary dormancy in oilseed rape genotypes under conditions of stress. Weed Res. 42(6):446–55. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3180.2002.00308.x.

Websites verified 7/16/2025

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

For additional agronomic information, please contact your local seed representative. Performance may vary, from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and environmental conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on their growing environment. The recommendations in this article are based upon information obtained from the cited sources and should be used as a quick reference for information about vegetable production. The content of this article should not be substituted for the professional opinion of a producer, grower, agronomist, pathologist and similar professional dealing with vegetable crops.

BAYER GROUP DOES NOT WARRANT THE ACCURACY OF ANY INFORMATION OR TECHNICAL ADVICE PROVIDED HEREIN AND DISCLAIMS ALL LIABILITY FOR ANY CLAIM INVOLVING SUCH INFORMATION OR ADVICE.

5016_585950 Published 07/17/2025