Click here to download a PDF version of this spotlight.

» Common smut can result in economic losses in sweet corn when disease-favorable conditions occur.

» A single smut gall on an ear of corn can make that ear unmarketable.

» Using smut-resistant varieties is considered the best method for managing common smut in sweet corn.

Common smut of sweet corn, also known as corn smut, is caused by the fungus Ustilago maydis, which can infect sweet corn, popcorn, field corn, and their wild relative teosinte. Common smut occurs worldwide on these various types of corn. Common smut has been shown to cause only minor damage to field corn in most years, with yield losses usually less than two percent. The disease can occasionally cause greater yield losses if environmental conditions are highly favorable for disease development.1,3,4

Economic losses from common smut can be greater on sweet corn because of the very low threshold for the disease and its effects on the marketability of ears for both fresh market and processing sweet corn. A single smut gall on an ear of fresh market sweet corn will most likely render that ear unmarketable, and entire fields of processing sweet corn may be abandoned before harvest if smut levels on the crop are too high.1,2

Interestingly, young ear galls can be harvested and eaten. The galls are known by the native Mexican name cuitlacoche (huitlacoche), pronounced like “wheat-la-coach-eh”. Cuitlachoche is considered a delicacy in parts of Mexico, sold fresh and canned, and can be found on the menu in some restaurants in the U.S.1,2

Figure 1. Galls of common smut developing on corn leaves. University of Illinois Extension

Figure 1. Galls of common smut developing on corn leaves. University of Illinois Extension

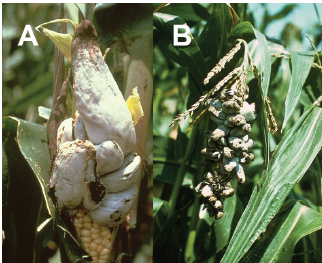

Figure 2. Common smut galls on corn (A) ears and (B) tassels. University of Illinois Extension.

Figure 2. Common smut galls on corn (A) ears and (B) tassels. University of Illinois Extension.

SYMPTOMS

All aboveground parts of a corn plant can be infected by the common smut fungus, including ears, tassels, stalks, nodal shoots, and the mid-ribs of leaves. Infection occurs on meristematic (growing) tissues. So, the location of galls depends on what parts of the plant are growing at the time the inoculum of the fungus lands on the plant. Early season infections will result in galls on leaves and stems (Figure 1), and later-season infections will result in galls on tassels and ears (Figure 2). Infections are only local, and the disease does not spread systemically within the plant.1,4

The tumor-like galls can be 0.4 to 12 inches in diameter, depending on the tissues infected. Gall will usually become visible two to three weeks after infection. Initially, the internal texture of the galls is spongy (mushroom-like), and the galls are covered with a white to greenish-white, semi-glossy skin. Galls mature over a period of 21 to 23 days, and during maturation, the interior becomes a wet mass of dark-brown to black spores called teliospores. Over time, the spore mass dries and becomes powdery. The outer covering becomes papery and brittle and ruptures, exposing the spore mass.1,2,4 Ear galls result from the infection of individual kernels, and these galls can grow up to twelve inches in diameter but are usually smaller. The infection of multiple kernels can result in multiple galls forming on the same ear. Early infection of a stem can kill a young plant.2,4

CYCLE AND CONDITIONS

Ustilago maydis overwinters as the teliospores produced in the galls. The teliospores do not infect other corn plants, and there is no plant-to-plant spread during the season. Teliospores can survive in the soil and on infested plant debris for many years. The spores can be spread by wind, splashing rain, and the movement of soil and crop debris, but they will not result in infection until the following season(s).

Under favorable conditions, the teliospores germinate and produce a second kind of spore called a sporidium (sporidia, plural).1,3,4 These sporidia also cannot infect corn plants on their own. When a sporidium germinates, it produces a germination tube that can fuse with a germination tube of a sporidium of a different mating type. (Mating types of Ustilago maydis are complicated, and we won’t go into that here.) The fusion of the two sporidial germ-tubes forms an infective hypha (fungal thread) that can infect the corn plant. For ear galls, this infective hypha grows down the silk channel and infects an individual, unfertilized kernel. Infection of other tissues is often most severe after wounding by blowing soil, hail, or other factors.1,4

Once they penetrate the plant, the fungal hyphae grow between the corn plant cells, absorbing nutrients, but the cells remain alive and intact. The hyphae cause the cells to grow abnormally, dividing and enlarging to initiate the growth of the gall.

Gradually, the hyphae grow and replace the plant cells in the gall. Eventually, the fungal hyphae transform into the teliospores that fill the gall.1,4 The conditions that favor smut development have not been well defined or documented. Some reports indicate that infection is more likely after periods of humid, rainy weather, while other reports say that the disease is more severe after dry periods.1,3,4 Thunderstorms and strong winds that blow soil can injure plants, resulting in sites of infection for the smut pathogen. Injury resulting from detasseling can also result in increased numbers of infections.

There is also some evidence that high levels of nitrogen fertilizer may result in vigorous growth of corn plants that may increase the chances of smut infection.4 Because ear galls result from the infective hyphae growing down the silk channel to infect unfertilized kernels, any factors that delay fertilization and prolong the presence of green silks can increase the likelihood of developing ear galls. Hot, dry conditions that result in reduced pollen production or asynchronous production of pollen and green silks can prolong the time that kernels are susceptible to infection. Once a kernel is fertilized, a barrier forms between the silk and the kernel, the silk dies, and infection can no longer occur.1,4

Teliospores are released when galls break open during the harvest of seed crops of sweet corn, and these teliospores may contaminate the harvested seed. However, teliospores do not infect the seed and are not able to cause post-harvest disease. Generally, common smut of corn is not considered seed-transmissible.4

MANAGEMENT

The primary method used to manage common smut in sweet corn is the use of smut-resistant varieties. While there are no sweet corn varieties with complete resistance to common smut, varieties do differ in their level of susceptibility. Smut resistance in corn (field, sweet, and pop) has been studied for almost 100 years, and partial resistance has been found in some inbred lines. However, the genetics of smut resistance are still not well understood, and major resistance genes have not been identified.1,3,4

Some disease and pest management guidelines recommend practices such as crop rotation, seed treatment or foliar fungicide applications, and fertility modifications (avoiding high nitrogen levels). Because of the biology of this pathogen, these methods generally have not been effective for managing common smut on sweet corn in areas where corn smut is established.1

SOURCES

1Pataky, J. and Snetselaar, K. 2006. Common smut of corn (syn. Boil smut, blister smut). The Plant Health Instructor 06, DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2006-0927-01. https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/pdlessons/Pages/CornSmut.aspx

2Jordan, T. 2024. Common corn smut. University of Wisconsin Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/common-corn-smut/

3Wyenandt, A. 2025. What’s up with corn smut? Plant & Pest Advisory, Rutgers Cooperative Extension. July 29. https://plant-pest-advisory.rutgers.edu/whats-up-with-corn-smut-2/

4Pataky, J. 2016. Common smut. In Munkvold, G. and White, D., Eds. Compendium of Corn Diseases, Fourth Edition. American Phytopathological Society.

Websites verified 8/18/2025

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

For additional agronomic information, please contact your local seed representative. Performance may vary, from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and environmental conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on their growing environment. The recommendations in this article are based upon information obtained from the cited sources and should be used as a quick reference for information about vegetable production. The content of this article should not be substituted for the professional opinion of a producer, grower, agronomist, pathologist and similar professional dealing with vegetable crops.

BAYER GROUP DOES NOT WARRANT THE ACCURACY OF ANY INFORMATION OR TECHNICAL ADVICE PROVIDED HEREIN AND DISCLAIMS ALL LIABILITY FOR ANY CLAIM INVOLVING SUCH INFORMATION OR ADVICE.

6711626000 Published 08/19/2025