Click here to download a PDF version of this Cultivation Insights article.

» Crop steering is the process of directing plants toward more vegetative or generative modes of growth and development.

» Cultural and environmental practices can be used to help steer crop growth.

» Crop monitoring (plant registration) can be used to help determine the current stages of crop development and provide information needed to make steering decisions.

As vegetable crops develop, their growth can vary on a continuum between vegetative and generative growth. During periods of primarily vegetative growth, plants put most of their energy into developing leaves, stems, and roots, while during periods of primarily generative growth, plants put more of their energy into producing reproductive parts (flowers and fruit). Early in the season, a plant’s energy is devoted almost entirely to vegetative growth as seedlings develop into more mature plants. As the season progresses, more energy is gradually shifted to supporting generative growth when the plant starts to flower and set fruit (Figure 1). However, especially for long-season greenhouse crop production, it is important to maintain some balance between vegetative and generative growth throughout the season. Steps may need to be taken to encourage more vegetative or generative growth depending on environmental conditions and the physiological state of the plants, a process known as crop steering.1,2

CROP STEERING

Vegetable crops can be steered in the direction of a desiredgrowth pattern with the use of several key inputs, including the following:

• Cultural practices such as leaf-removal, pruning, vinelowering, and harvesting

• Environmental modifications, including light, temperature, humidity, and CO2 levels

• Adjusting nutrient concentrations and the frequency and duration of irrigation

Providing the right conditions at each stage of cropdevelopment can help maximize crop growth and yield potential. Maximizing yield potential may be assisted by steering toward more vegetative growth pattern during the early stages of development and toward more generative growth during the flowering and fruiting stages. Gradual steering has shown to be a best practice; don’t immediately switch from environments that promote vegetative growth to ones that promote generative growth after the start of flowering.2

Steering the crop too far in the direction of generative growth can result in crop stress, excessive loads of small fruit, weak plants, increased susceptibility to disease, and ultimately reduced production. Steering the crop too far in a vegetative direction can result in an abundance of leaf and stem growth but little flower and fruit production. However, the goal is not to keep a 50/50 balance of growth at all times.1,2,3 Adding stress will generally steer the plant to more generative growth, while removing stress has shown to steer toward vegetative growth.3 Best practice is to make gradual changes and see how the plants respond. The development of nutrient deficiency symptoms, slowed plant growth, reduced fruit set, or smaller fruit size are indications that the push toward generative growth went too far and that pulling back somewhat may be necessary.

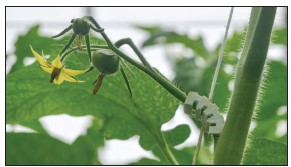

Figure 1. The development of flowers and setting of fruit is evidence of generative plant growth.

Figure 1. The development of flowers and setting of fruit is evidence of generative plant growth.

Temperature affects the rates of photosynthesis and respiration of the plants, and adjusting greenhouse temperatures is one way to help steer plant growth. At low temperatures and high humidity, there is less demand for assimilates, which may result in more leaf and stem growth (more vegetative). At higher temperatures, plants produce a higher fruit load and fastergrowing tips (more generative). Lower average temperatures can be used to promote more vegetative growth early in the season, while higher temperatures later in the crop cycle promote fruit development. Increasing the day/night temperature differential and the day-to-night cooling rate also tends to increase generative growth.3,4 Irrigation frequency and duration affect water and nutrient uptake. Generally, more water is needed during the vegetative growth stages, and less water will encourage fruit development.3 Reducing the amount of water applied stresses the plants and pushes them toward generative growth. Humidity also plays a role, as water uptake is reduced at high humidity levels. Each of these practices/conditions places more stress on the plant, encouraging increased effort toward flower and fruit production. Pruning leaves, flowers, and suckers also helps redirect energy toward more generative growth.2

Lower light levels can promote vegetative growth early in the crop cycle, and supplemental lighting may be needed to provide adequate amounts of light to support crop growth. Higher light levels later in the crop cycle can promote more flowering and fruit production, but may result in a push too much in the generative direction. Light levels can be managed by adjusting the distance between plants and the light source, the duration of exposure, and the light intensity. The use of shade cloth, whitewash, or shading materials can be used to lower light levels and promote more balanced growth and fruit development.3

PLANT REGISTRATION (MONITORING)

Periodically measuring plant growth helps growers determine the vegetative and generative growth trend, allowing them to initiate strategies to better steer the plants to the desired state of balance on the vegetative-generative growth continuum.4 The term plant registration (crop registration) is used to indicate regular measurement, recording, and analysis of crop development indicators.2 Some growers designate specific blocks of plants in each zone of the greenhouse to be monitored on a daily to weekly basis. Some direct plant measurements that are taken include weights of fruit clusters, internode lengths, weekly stem growth, head width (stem diameter beneath the youngest flower cluster with an open flower), and numbers of new leaves. Environmental data is also recorded, including day and night average temperatures, EC drip and EC drain values, irrigation start and stop times, and irrigation rates.2,5

Crop registration has relied on the practice of manually measuring and recording vegetative and generative plant characteristics. This is usually done with a small sample of plants representing various sections of the greenhouse. The goal of registration is to base steering decisions on leading indicators of growth rather than trailing indicators, such as yield. In this way, problems can be identified early and decisions can be made to adjust to developing situations.1

Direct measurements require physical contact with the plants to determine values for plant height, stem diameter, height of flowering truss, weekly growth, youngest flowering truss, youngest setting truss, youngest harvested truss, leaf length, and flower size. Some environmental measurements can be taken remotely, such as temperature, humidity, light conditions, and plant water use.5,6 Remote, automated measurements can be taken daily, or more often, but the time and labor requirements associated with direct measurements often limit sampling to once a week. Small sample sizes and low sampling frequencies can result in inaccuracies in the evaluation of the condition of the whole crop, resulting in growers making less appropriate decisions.1

For several years, growers, researchers, and the greenhouse support industry have been looking into ways to automate the process of crop registration. Automation can allow more plants to be monitored and measurements to be taken more frequently.1 One method being investigated for remote measurement of crop growth is the use of cameras and machine vision technology to measure seedling height, total leaf area, and relative growth rates. The data can be used to estimate top fresh and dry weights, leaf sugar content and rates of photosynthesis, and to predict developmental stages, such as time to first flower, that can help in crop maintenance scheduling.6,7,8 Video imaging is also being used to document the growth rate, shape, and color of fruits. These systems may also be able to help detect the early stages of problems such as blossom end rot. Imaging and machine vision systems may also be able to help monitor leaf mineral content, nutrient deficiencies and toxicities, water stress, and low temperature responses of the crop. However, machine vision systems can be expensive, and the technology is still in the developmental stages. With further research and development, the use of automated systems to monitor crop growth and conditions may become a widely used means of helping to make accurate crop steering decisions.

SOURCES

1Verrier, E. 2025. Crop registration: A compass for crop management. IUNU. https://iunu.com/resources/crop-registration.

2Gagne, C., Kovach, D., and Mattson, N. 2021. Learn the basics of greenhouse tomato crop steering. Greenhouse Grower. https://www.greenhousegrower.com/production/learn-the-basics-of greenhouse-tomatocrop-steering/.

3 2023. Crop steering 101: How to optimize tomato growth for maximum yield. Way Beyond. https://www.waybeyond.io/resources/crop-steering-101-optimizing-growth-for-maximumyield.

4 2023. The important role of plant balance in tomato crop steering. Way Beyond. https://www.waybeyond.io/resources/the-important-role-of-plant-balance-in-tomatocrop-steering.

5Why Crop Registration Matters – e-Gro customer case video’s. https://www.grodan.com/global/knowledge/blogs/Why-Crop-Registration-Matterse-Gro-customer-casevideos/#:~:text=Crop%20registration%20is%20the%20process,consistently%20on%20a%20weekly%20basis.

6Ehret, D., Lau, A., Bittman, S., Lin, W., and Shelford, T. 2021. Automated monitoring of greenhouse crops. Agronomie 21:403-414. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2001133.

7Rahman, F. A., Takanayagi, M., Eguchi, T., Yeoh, W. L., Yamaguchi, N., Okumura, H., Tanaka, M., Inaba, S., and Fukuda, O. 2024. Growth monitoring of greenhouse tomatoes based on context recognition. AgriEngineering, 6(3), 2043-2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering6030119.

8Polder, G., Dieleman, J., Hageraats, S., and Meinen, E. 2024. Imaging spectroscopy for monitoring the crop status of tomato plants. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Volume 216: 108504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108504.

Websites verified 5/6/2025

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

For additional agronomic information, please contact your local seed representative. Performance may vary, from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and weather conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on their growing environment. The recommendations in this article are based upon information obtained from the cited sources and should be used as a quick reference for information about greenhouse cucumber production. The content of this article should not be substituted for the professional opinion of a producer, grower, agronomist, pathologist and similar professional dealing with this specific crop.

BAYER GROUP DOES NOT WARRANT THE ACCURACY OF ANY INFORMATION OR TECHNICAL ADVICE PROVIDED HEREIN AND DISCLAIMS ALL LIABILITY FOR ANY CLAIM INVOLVING SUCH INFORMATION OR ADVICE.

5010_563050 Published 05/12/2025